Lakeland is immortalized in digital form with help from MITH and INFO.

Lakeland Road near Rhode Island Avenue circa 1965. Photo courtesy of Lakeland Digital Archive

Lakeland is a 130-year-old African American community adjacent to the University of Maryland that had much of its landscape demolished during urban renewal in the 1970s, displacing nearly two-thirds of its residents. Before urban renewal, Lakeland was a close-knit community with quaint, tidy homes nestled amidst boughs of mature oaks, ash, and elm trees. In the summer, elders sat on brick porches while children chased fireflies in the humid evenings. Churches were a bedrock of support and a space for socialization—in preparation for community events, the smell of home-cooked food wafted from their kitchens.

Local businesses lined a street—corner stores and mom-and-pop shops showcasing their displays of goods. While the community faced the challenges of segregation and inequality, that was never the defining element of Lakeland.

For the past two decades the Lakeland Community Heritage Project (LCHP) has worked to collect and preserve Lakeland’s history, gathering thousands of historical records from the community, including historical maps and correspondence, along with oral histories and other documentation, including photographs and pamphlets from major events. In 2018, LCHP partnered with the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), along with faculty and students from the College of Information Studies (INFO) and the Department of American Studies at University of Maryland to prototype a digital community archive, which is currently in development.

Institutional archives—such as those found in museums, libraries, and universities—tend to focus on privileged individuals and groups and often contain silences about the lived experiences of marginalized peoples. Community archives, like the Lakeland Digital Archive, seek to remediate those silences and aim to document and celebrate everyday stories and empower underrepresented communities to tell those stories on their own terms, without bias or sanitization. Yellowed newspaper clippings, a sepia-toned portrait, a recipe passed down through generations—these are just a few of the artifacts one might find in a community archive.

“Community archives are any kind of collection that a community puts together to serve its own needs, whether as a locus of memory or of shared information about identity or shared history,” says Katrina Fenlon, INFO assistant professor. “Community archives can be built around all kinds of dimensions of how people experience the world—around belief systems, gender identity, all kinds of things.”

Visualizing Historic Lakeland

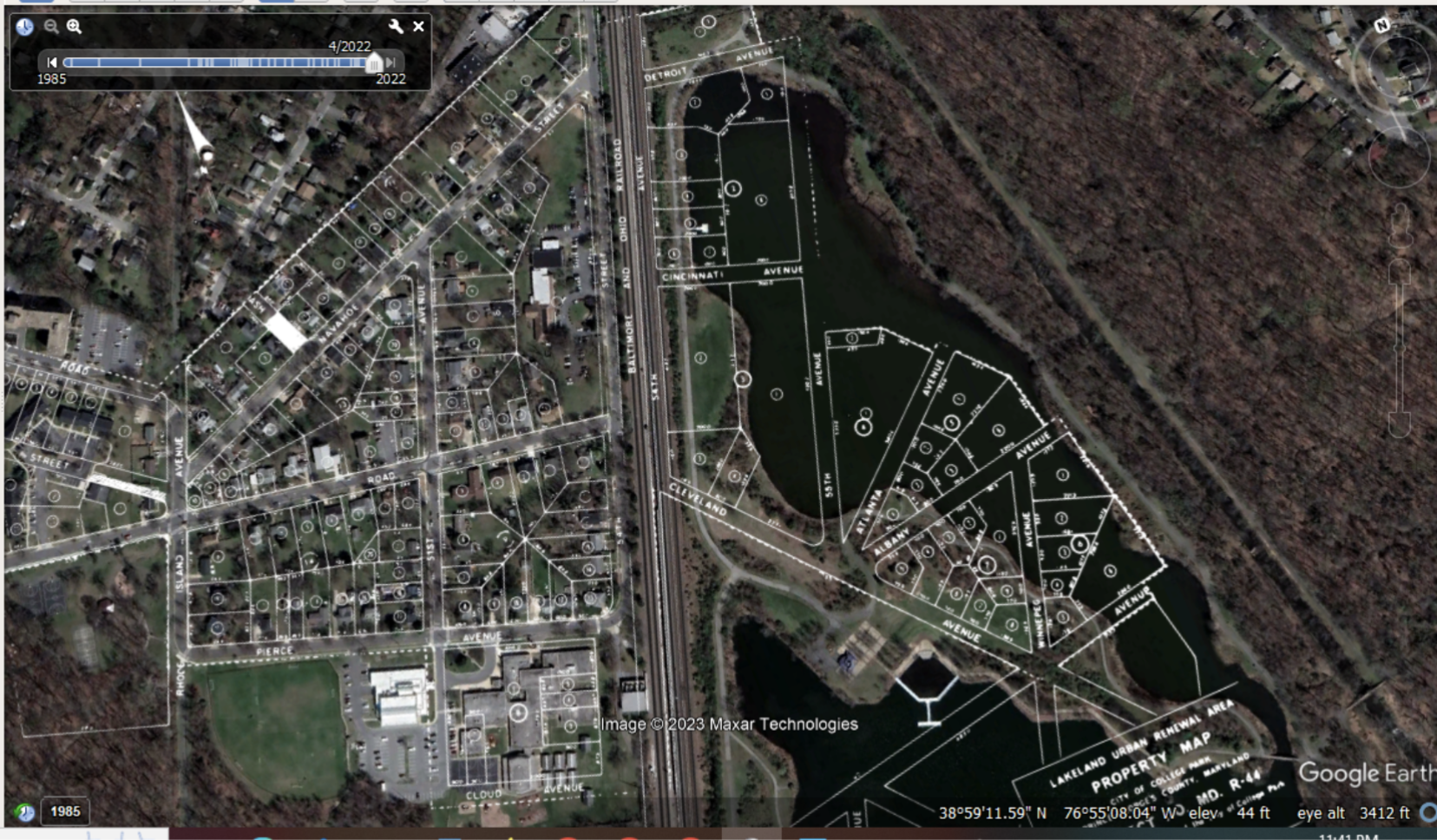

Fenlon teaches several courses, including Metadata and Tools for Information Professionals as well as Implementing Digital Curation, that facilitate projects for the Lakeland Digital Archive. Students help improve metadata so that artifacts are better linked to the broader web of cultural heritage data that exists on the internet. Last semester, they worked with geospatial data—how places are represented in the archive—and produced a set of visualizations of historic Lakeland overlaid on a present day map so that you could see the lost properties.

INFO students Dana Getka, Anna Gormbley, Sara Riley, and Melody Wang created the map.

The Broader Mission of the Archive

In describing the impetus for the archive, Maxine Gross, chairperson of LCHP says, “Our concern was that the stories of our grandparents and parents would be lost if we didn’t do something to capture them and the essence of the community.”

In 2002, during a local Emancipation Day event, LCHP started gathering materials from the community for the archive. Those materials were digitized and stored on hard drives that sat on bookshelves or in closets for years until the recent buildout of the website.

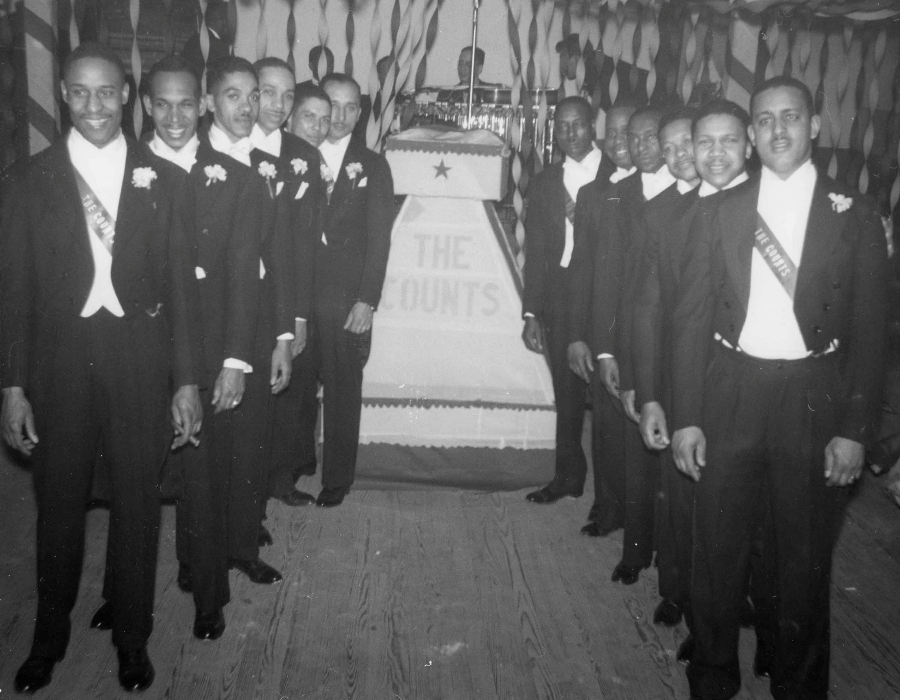

The archive holds rich stories—some of which are told through photographs. A photo of a group of men dressed in tuxedos stands out to Gross as one of her favorite artifacts. They are members of a social club called the Counts. The men invented the club for themselves because most of the clubs in the area were not open to Black people.

“Most did domestic employment; some were federal clerks. They were extremely limited in their opportunities and their place in society,” says Gross. “Through this club, they defined who they were and how they wished to present themselves. They presented themselves with dignity and what they considered class.”

The Duchesses and the Counts social clubs sponsored an annual formal dance at Lakeland Hall and sometimes posed for professional photographs. The Counts appear here in formal tails and white gloves. The gentlemen are, left to right (left row) Gasson Bradford Sr., James Weems, Anderson Walls, George Walls, Charles Carroll, and Harry Braxton Sr.; (right row) Mack Allen, John Webster, William Sharps, Aubrey Corprew, Chesley Mack, and Ashby Tolson. Photo courtesy of Lakeland Digital Archive.

The value of the archive extends beyond the moments it immortalizes. It documents the historically harmful effects of the creation of high-rise architecture and train tracks that divided and separated the community from nearby neighborhoods and local amenities. In this way, it informs present-day development decisions related to transportation, zoning, and land use.

The LCHP’s efforts to spread awareness about the history of the community has also given rise to a restorative justice initiative in the city. “It is one of the first digital archives to turn the archive into action for the community,” says Fenlon. “The City of College Park has a committee that is considering reparations for Lakeland. It makes College Park one of the first cities in the nation to consider reparations for harms done during urban renewal. The Lakeland Digital Archive has been at the heart of that, and it’s because the archive is the home base for telling the community’s story in a persuasive way and helping people understand what happened.”

Maintaining Ownership of the Collection

Community archives—among other sites of grassroots knowledge production—are notoriously difficult to sustain over time. They tend to be maintained outside of institutions, by small teams of volunteers, yet they hold unique cultural evidence of enormous value. Fenlon’s research, in collaboration with the Lakeland Digital Archive and several other projects, focuses on the roles of communities in sustaining digital archives. Funded by awards from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, her work explores what it means to truly center the endurance and preservation of community-based collections within communities themselves. Fenlon’s work sheds light on approaches to community-centered sustainability, which take community ownership and power meaningfully into account, and do not rely exclusively on handing off responsibility for collections to preservation institutions like libraries and archives.

The Lakeland community expects to maintain ownership and control over how the digital archive is represented and contextualized. They hope to expand its collection and engage a wider audience while maintaining a strong central organization, the LCHP, to represent the archive and connect with its constituents. They aim to use the archive as a foundation for social and political initiatives, involving peer communities and institutional partners. Community members prioritize the sustainability of the archive in relation to the community’s future and well-being, rather than solely its technical existence.