Morphic, a new computer operating system extension developed by iSchool researchers, includes an interface feature called the QuickStrip that improves accessibility by adjusting text size or spacing, reading text aloud and more.

Information science major Meagan Griffith ’20 spends so much time peering at a computer for her studies that she often suffers from eyestrain. But because of the fussy and confusing settings menus of computers, she’d never given much thought to adjusting contrast or brightness to give her eyes a break.

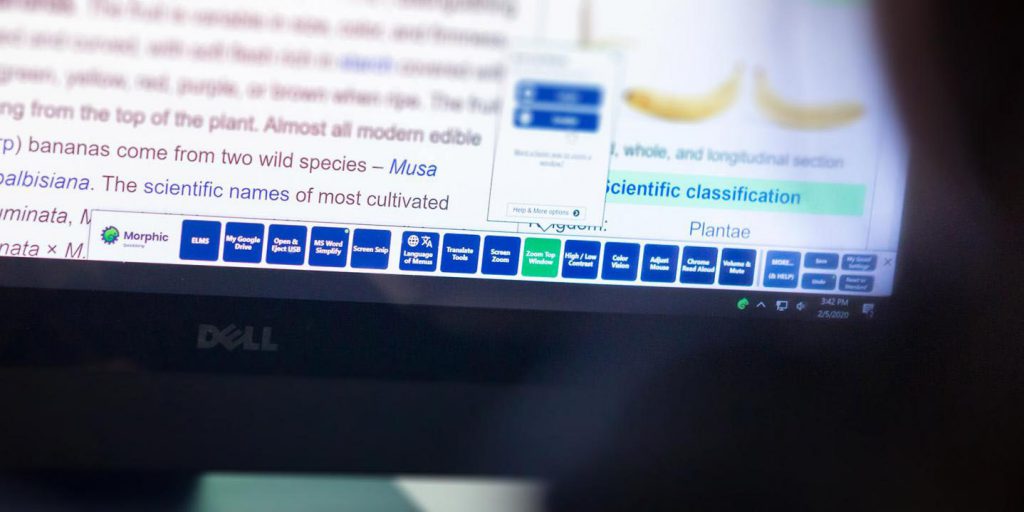

That is, until she became a tester for Morphic, a new computer operating system extension with accessibility and customization in its digital DNA. Developed by an international team led by College of Information Studies researchers, it debuts today on all Windows computers in the McKeldin, STEM and Michelle Smith Performing Arts libraries. An interface feature called the QuickStrip sits conveniently at the bottom of the screen, and helps Griffith change her settings without breaking focus.

“I always know right where it is,” Griffith said. “I don’t have to open settings and navigate away from what I’m doing, especially if I’ve been doing an assignment for a while and am bored and easy to distract.”

Morphic is a product of UMD’s Trace Research & Development Center, which has played a role in improving accessibility in computers, phones and other devices used throughout the world. The system can help people with vision or reading problems by adjusting text size or spacing, or even reading text aloud, while it has more tricks up its sleeve for people with mobility challenges or other physical limitations or disabilities.

It’s always running, even if you opt to hide the QuickStrip toolbar, and offers quick-access buttons to a variety of things—volume, USB drive, text size, screen capture—that each user can set and forget. Settings are saved to a cloud and automatically take effect when you sign-on to any Morphic-enabled computer (and when you sign off, the computer resets to its standard settings for the next user.)

Computers and high-tech gadgets are more powerful and offer more functions than ever, but there’s a drawback to all this innovation—sometimes they seem to require a computer science degree and three hands to use effectively. People with physical, neurological and other challenges face higher hurdles than typical users.

“We’re designing stuff that is all really complicated. We are literally disabling people with the complexity,” said Gregg Vanderheiden, Trace director and a principal investigator on Morphic. “We need to be figuring out how we can create things that are easier for people to use rather than harder.”

For example, the numerous menus and commands in Word are “way too complicated,” Vanderheiden said. The QuickStrip offers a simplified Word with only the essential buttons.

Morphic is just getting started. Later this spring, Trace plans to offer the software for Macs as well as campus-wide—even on users’ personal computers with a link called “I want to take this home.”

The Trace Center collaborated with UMD Libraries to support this technology. Babak Hamidzadeh, associate dean for digital services and technologies at UMD Libraries, said the library system, with its wide-ranging user base, was a natural place to pilot Morphic.

“We are all about wide and open reach to all of our constituents, and this definitely afforded us that wider range of usability for our computers,” Hamidzadeh said.