MLS alumnus Ariel Segal worked on the years-long project

Ariel Segal (at center) and colleagues from around the world, including head of the Library of Congress Collections Digitization Division Tom Rieger (at right), at the Society for Imaging Science and Technology Archiving 2024 Conference at the National Archives celebrate after Segal's Hebrew Manuscripts presentation

Delicate manuscripts from the Middle Ages kept in temperature controlled locked cages in locked rooms to preserve their integrity aren’t usually seen by the untrained public. Thanks to a massive digitization project conducted by a team of archivists and imaging specialists at the Library of Congress, that is changing.

The Hebraic Section of the Library of Congress possesses some 230 manuscripts in Hebrew and similar languages. This extensive collection, which spans from the High Middle Ages through the modern era, offers a window into the rich tapestry of Jewish thought, culture, and daily life across centuries. University of Maryland College of Information Studies alumnus Ariel Segal, who received his Master’s in Library Science in 2005 together with a Master’s in History, is an archivist who worked on digitizing this massive collection. Segal and his team used Phase One 100-megapixel camera systems to capture the manuscript images. This was followed by meticulous post-processing—including cropping and de-skewing via Capture One professional photo editing software. The post-processing phase was followed by the use of the Golden Convert Color Management system, a sophisticated digital processing tool designed to ensure accurate color reproduction.

“The library acquired updated state-of-the-art digitization equipment as part of the relocation renovation of its digital scan center during the pandemic, and new techniques for color management are now available,” says Segal. “And the library therefore decided to digitize the library manuscripts at high resolution and release them to the public in a digital form, much closer to the actual physical objects, in terms of both resolution and color.”

Collection Highlights

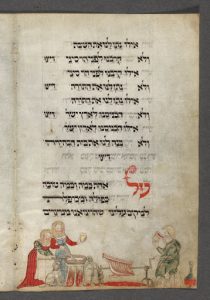

Leaf from Hebrew Manuscript 181, Washington Haggadah, depicting women preparing Passover meal, with dog at their feet. 15th century.

The collection encompasses a diverse array of documents, from religious texts and legal codices to scientific treatises, literary works, and intimate personal letters. This breadth highlights the multifaceted nature of Jewish life and provides scholars across various disciplines with a profoundly rich resource for research and education.

“I was able to use my fluent Hebrew skills and knowledge of Jewish culture to ensure the manuscripts were digitized in an accurate order, and understanding the nature of what I was preserving gave a deeper appreciation of how important this project was. I consider it one of the supreme highlights of my career,” says Segal.

Among the collection’s highlights is the famous Washington Haggadah, a late 15th-century gem known for its striking illustrations that detail the Passover service. This Haggadah is particularly noted for its vibrant depictions of daily life, including images of women preparing for the Passover feast, complete with a dog at their feet, adding a charming glimpse into the communal and familial aspects of Jewish life during that period.

What the Scans Revealed

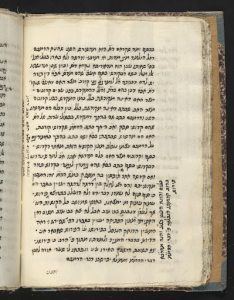

Leaf 26r from Hebrew Manuscript 31, “Responsum on the validity of the kiddushin (betrothal) of two daughters…” 17th century. Note exposure of previously unseen autograph gloss by R. Moses Benveniste including Hebrew “safek kiddushin” (doubtful betrothal).

The digitization of historical manuscripts can unveil details that were previously hidden or overlooked, as demonstrated by the treatment of a document that was part of a genre where rabbis address legal questions. This one dealt with the betrothal of two daughters. While the manuscript had been preserved through microfilming, the technology had its limitations. It was not until the manuscript underwent a more advanced digitization process that the true depth of the document came to light.

The scanning technology was able to expose additional text within the gutter of the manuscript, a section that the microfilm version had failed to capture clearly. This newly revealed text offered a significant insight: one rabbi’s commentary on another’s legal argument was “doubtful betrothal.” This gloss exposed a layer of scholarly debate and interpretation that was essential for a complete understanding of the manuscript’s content.

Challenges and Opportunities

Digitizing historical documents can present unexpected challenges. For Segal’s team it was the temperature of the scan center. During the early days of the project, the team made an unfortunate discovery: the operation of all the scanning machines simultaneously would raise the temperature inside the center to a stifling 85 degrees. To mitigate the temperature issues and ensure the safety and efficiency of the digitization process, a decision was made by the head of the team, Tom Rieger, to undertake construction efforts aimed at enhancing the ventilation and cooling systems within the scan center. This construction, which spanned over a year, substantially impacted the project’s timeline. Despite the setbacks, the project is now complete, in time for Jewish American Heritage Month in May. Segal and his colleague Hana Beckerle, who provided an excellent workflow to ensure the project was completed efficiently, gave a presentation about the project at a major imaging conference in April.

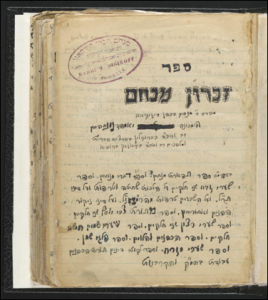

Title page from Hebrew Manuscript 224, Sefer Zikhron Menahem, by Rabbi Menahem Risikoff, 20th century.

“This project will allow for researchers and the public to access all these manuscripts online without having to come to DC in person,” says Segal. “Images can be rotated and zoomed in on the library website. They were scanned at 400 dots per inch, so the detail can be examined in depth.”

Segal found it particularly meaningful when he digitized Hebrew manuscripts by Rabbi Menahem Risikoff, a rabbi who was his good friend’s wife’s great-grandfather. Her uncle, noted Navy chaplain Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, donated the manuscripts to the Library in 2010.

One researcher who might make use of the archive is Professor Avi Shmidman from Bar-Ilan University in Israel. Shmidman is planning to use online archives of Hebrew manuscripts to train artificial intelligence (AI) on optical character recognition (OCR). Traditional OCR technologies, which excel with printed or typewritten texts, often don’t work when faced with the unique characteristics of manuscript writing, such as variations in handwriting, ink bleed, and the condition of the paper. Because these manuscripts are clearer, sharper, and of higher resolution than ever before, AI-driven OCR efforts will be more successful, enabling automated transcription, which will facilitate a wider range of research activities.

The promise of AI underscores the dynamic interplay between technology and the humanities. As Shmidman’s project progresses, it will undoubtedly shed new light on old texts, opening up avenues for exploration and understanding. Digital preservation is enriched by such endeavors, demonstrating the endless possibilities that arise when technology meets history.