Doctoral Student Delves Into Dark Humor About Global Challenge

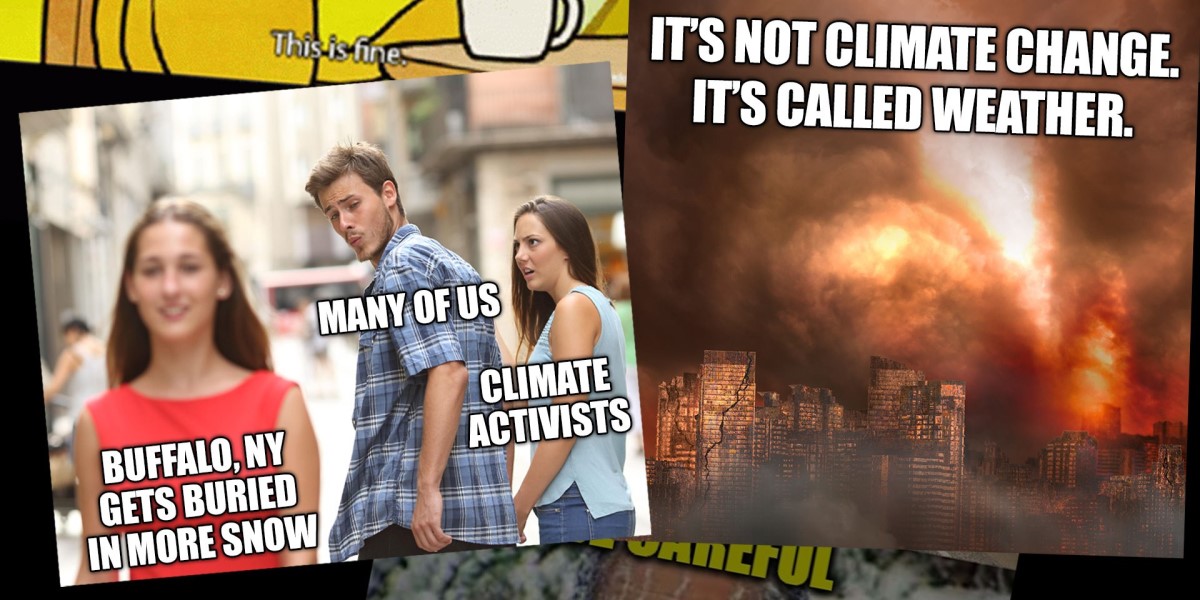

Disloyal boyfriend photo by Alamy; city photo by iStock

A hungry polar bear crouched on a tiny iceberg might not seem like comedy gold. But throw a couple of snarky, block-lettered words on it, and it might just become the latest post on social media that makes you go, “Hah.”

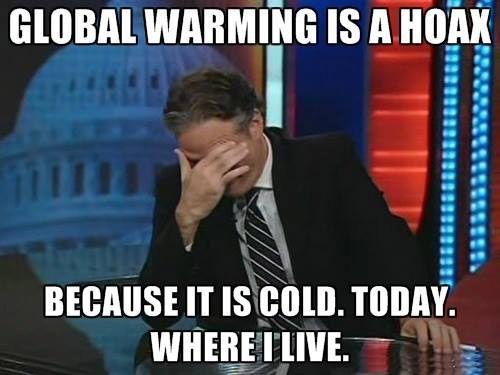

While memes are easy to dismiss as low-effort jokes—we’ve all seen the same image of Drake with his hand up or the guy ogling a female passerby as his girlfriend glares at him—in reality, they’re an easy way for people to spread facts as well as misinformation.

“In just the glimpse of an eye, they catch something emotional in you. That emotion almost overwhelms your thinking, and people have a tendency to repost and share with their friends,” said Jeff Henrikson, a lecturer in the University of Maryland’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science who is studying climate change memes for his doctorate in information science.

He’s examining ones created by both ends of the political spectrum, searching for common themes and differing approaches via Facebook groups and Reddit forums.

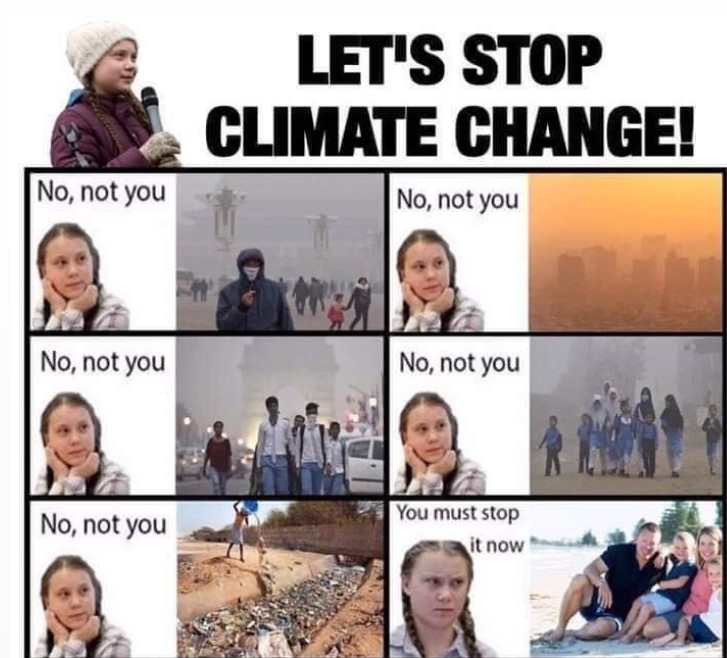

So far, Henrikson has found that liberal takes are often aimed at corporations or general topics like carbon capture (pulling warming gases from the air), while conservative ones tend to go for more personal attacks, such as on U.S. Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), Swedish activist Greta Thunberg or President Joe Biden. Memes on both sides also poke fun at initiatives that seem like wasted efforts, such as “greenwashing” by companies that merely pay lip service but do little to actually reduce harmful emissions. He hopes that his findings can help people step out of their “echo chambers” and present factual information more effectively to reach the other side.

He’s also incorporated memes into one of his courses, “Causes and Consequences of Global Change.” “Before I took it over, it used to be very heavy on the sciences,” said Henrikson, who has taught introductory science classes for about two decades. “I wanted to focus on how society is dealing with and approaching climate change, and memes were a way into that.”

Giving students the chance to go on social media for class, but with a critical eye, makes climate change more of an accessible topic for them. They’re tasked with finding and evaluating memes for credibility, just as they learn to do for news stories and videos they see online.

His students have grown up in an era where apps and websites make it easy to put together slick graphics, so “they often walk in with the idea that if it looks professional, it must be accurate,” Henrikson said. “But then I show them faculty websites that are still using HTML from 1998, or nonprofit sites that have distracting advertising because they need the money, to help them understand that their initial gut reaction isn’t necessarily a true measure of how credible a source is.”

He shares his thoughts on several memes he and his students have found:

This addresses one of the biggest misconceptions about global warming: the difference between weather in specific locations and climate for the entire planet. “Individual snowstorms during individual years—like this year, California has been incredibly wet—doesn’t mean the drought’s over or that warming isn’t happening,” Henrikson said.

“This goes after Greta Thunberg for not addressing developing countries with their emissions—only rich white people,” Henrikson said. “This is a common theme in conservative memes: Why should we in America have to do anything if the rest of the world isn’t going to do it, when actually, the developing world is having the worst impacts and the least financial ability to deal with the changes we’re experiencing?”

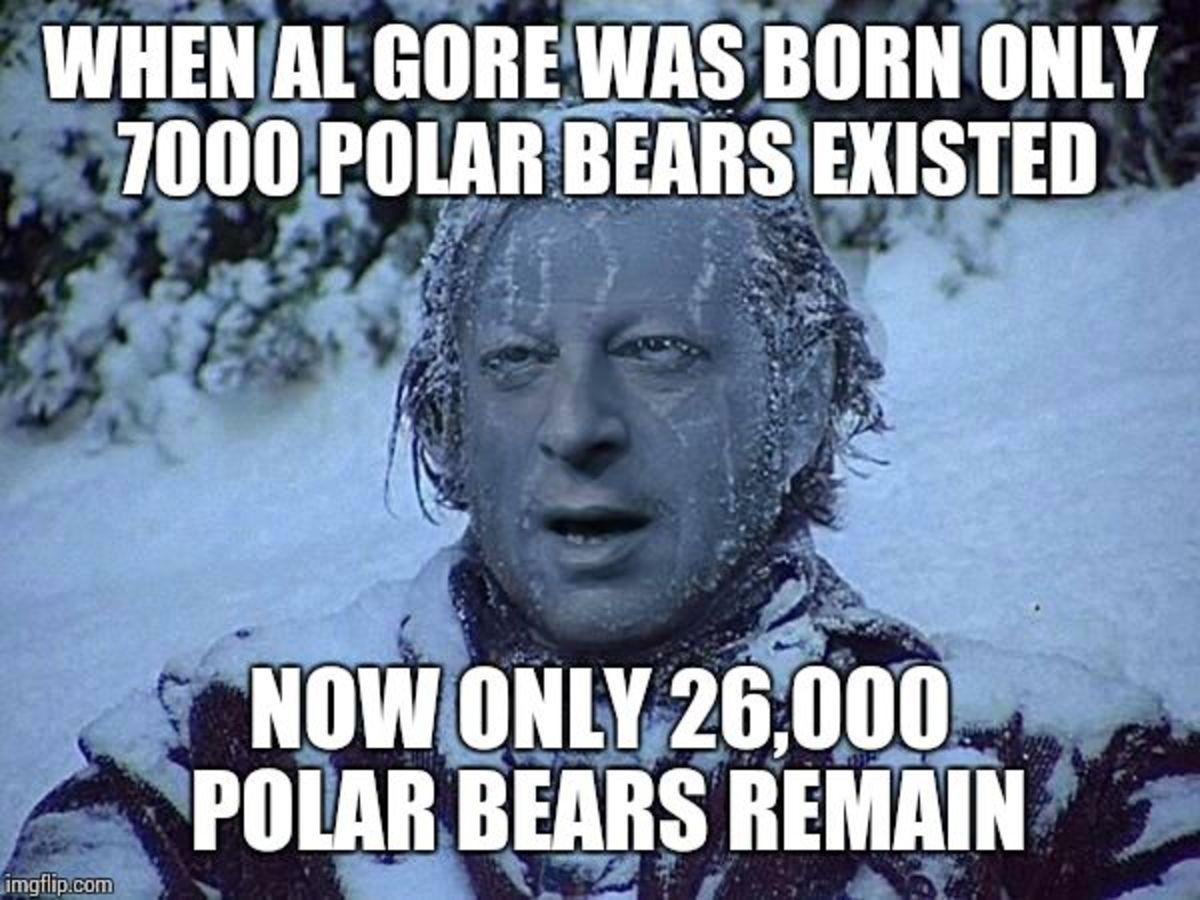

The snark in this meme, showing Al Gore’s face over Jack Nicholson’s frozen body in “The Shining,” mocks the former vice president’s climate advocacy, implying that his concern about the shrinking number of polar bears in the 1990s was unwarranted. “We stopped hunting of polar bears, so their populations have grown,” Henrikson said, but that doesn’t mean they’re doing fine. “They are threatened by other things now,” such as the steady loss of sea ice from which to hunt.